Getty

GettyThe New York Times Connections game asks players to categorise 16 words into four groups of four. For example, in one collection of 16, a category included “blow”, “cat”, “gold” and “sword”: these are all words that might come before “fish”.

As described by puzzle editor Wyna Liu, completing the puzzle should feel “challenging and satisfying”. Players are encouraged to “think flexibly”. Liu says her job as puzzle designer is “to trick you”.

Challenging word-based games are not a modern invention.

In fact, in early medieval England, around the year 1000, there was also a strong appetite for word puzzles designed to entertain (and trick) avid players.

Gaming in the Middle Ages

Riddles were very popular in early medieval England.

Many examples of riddles from this period are in Latin, but a collection of approximately 95 poems, written in Old English and found in a manuscript known as the Exeter Book are the earliest surviving vernacular collection of riddles in Western Europe.

Compiled around the year 1000, The Exeter Book also includes a variety of poetic works with both religious and secular themes. This, and its location since 1072 in Exeter Cathedral Library, suggests it had a religious audience of monks.

Take the shortest riddle in the Exeter collection, Riddle 69, included here in both its original Old English form and in translation, thanks to riddles scholar Megan Cavell, one of the creators of the website The Riddle Ages:

Wundor wearð on wege; wæter wearð to bane.

There was a wonder on the wave; water turned to bone.

Early English riddles ask their audience to guess what the different clues point to, usually an object or animal. In Riddle 69, the audience is asked to identify what might be referred to through the metaphor of water turning to bone.

The solution to this riddle is debated, but most suggestions have to do with ice: ice, icicle, iceberg and frozen pond.

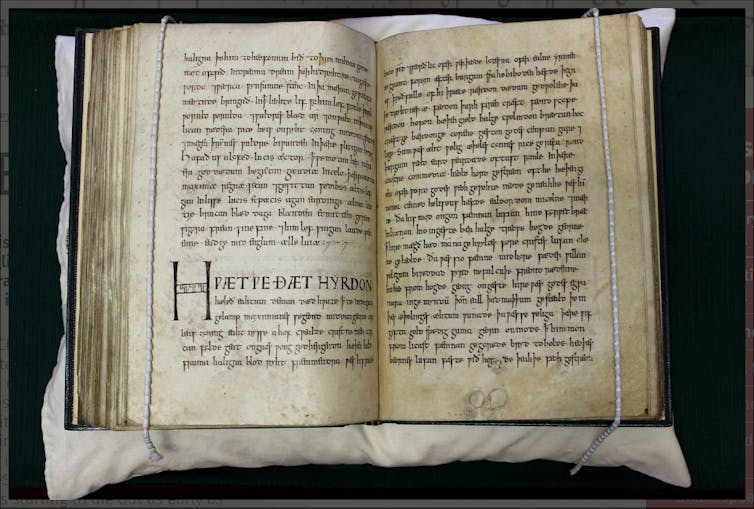

The Exeter Book is a 10th Century poetry anthology written in Old English.

Per Se/Flickr, CC BY-SA

The Exeter Book is a 10th Century poetry anthology written in Old English.

Per Se/Flickr, CC BY-SA

The answer hangs on the various qualities that attach to the word bone: it is hard, difficult to break and can also be long, like an icicle.

It’s possible to imagine bone and ice linked in a Connections category “things that are tough”.

Most Old English riddles are a little more complex but still rely on the trickery that comes from word play, metaphor and ambiguity.

One of the more surprising riddles in the Exeter collection (particularly when we consider the likely monastic audience) is Riddle 45:

I heard that something was growing in the corner, swelling and sticking up, raising its roof. A proud bride grasped that boneless thing, with her hands. A lord’s daughter covered with a garment that bulging thing.

A series of clues point to possible solutions. The answer will be something that rises, that needs physical touch to grow, and which is covered by cloth.

The innocently playful solution to this riddle is dough – though it certainly puts another, more vulgar, solution in mind. This innuendo likely added to the entertainment and challenge of the original riddle, teasing its audience with a taboo answer.

The Exeter Book Riddles does not come with answers. This is both a frustration and a reason for their longevity: modern audiences continue to grapple with possible solutions 1,000 years later.

It is also possible that part of the entertainment for both medieval and modern audiences is their ambiguity. There are multiple plausible solutions.

Culture is a game changer

Part of what makes interpreting the Old English riddles so difficult for modern players is that word puzzles are shaped by the culture in which they were created.

This cultural coding is obvious in Connections puzzles too. For example on January 3 2025 a category linked American slang words for a dollar, less familiar in other countries: buck, clam, single and smacker.

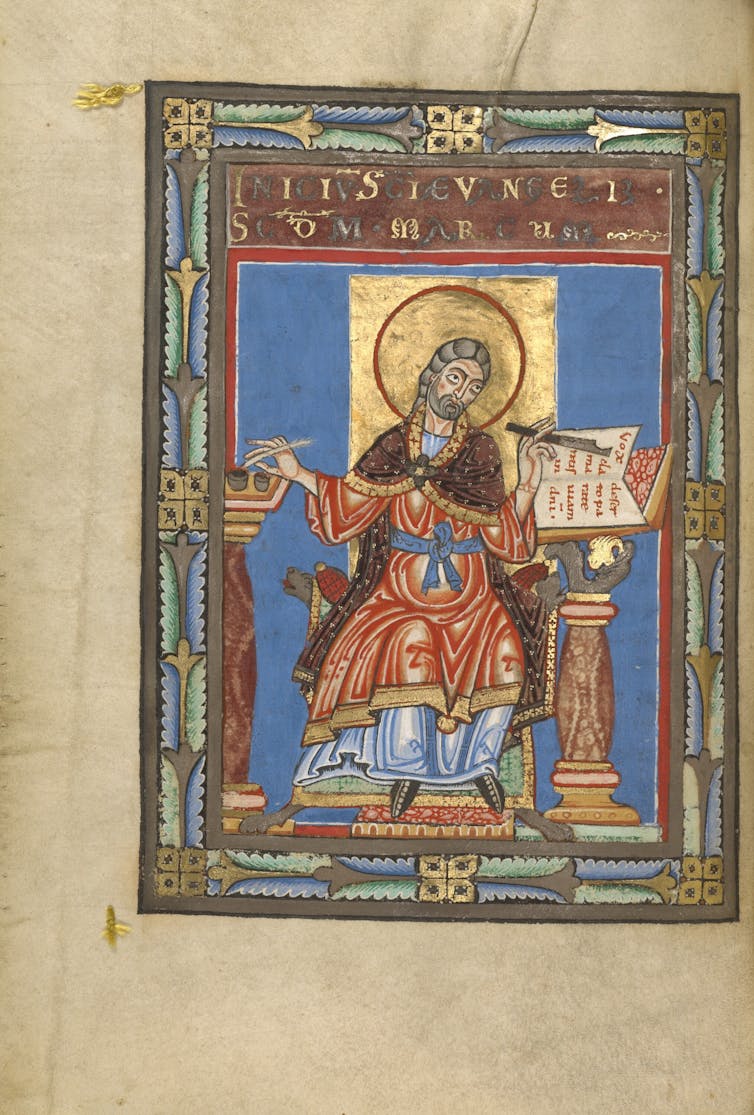

Similarly, Old English riddles assume knowledge of aspects of life in early medieval England. For example, Riddle 26 requires an understanding of the processes by which an animal hide became a book.

Some even rely on knowledge of runic characters to understand their solution; this was an alphabet that was used in England prior to the adoption of the Latin alphabet from the 7th century.

To truly understand many riddles, you need to know the context in which they were written.

Getty

To truly understand many riddles, you need to know the context in which they were written.

Getty

Old English riddles offer an excellent insight into not just the sorts of games and puzzles that entertained early medieval audiences, and continue to entertain us today, but also into domestic life in the period.

In 1,000 years, Connections puzzles will be harder to guess because players will be unfamiliar with our current way of life. They will also be a type of relic into how minds and culture operated in the early 21st century.

Emma Knowles does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

2 months ago

425

2 months ago

425

English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·