Pixabay/Pexels

Pixabay/PexelsAfter writing and selling a “dark romance” novel, a self-published author from Quaker’s Hill will appear before a Sydney magistrate on Monday, charged with producing, possessing and disseminating child sexual abuse material. The Daily Telegraph reported police had “received multiple complaints”.

Before New South Wales police arrived at her doorstep, the author, revealed on Booktok as Lauren Tesolin-Mastrosa, posted a dismayed apology on her Instagram account, now taken down but reproduced by News.com. It was a “huge misunderstanding”, she wrote. Daddy’s Little Toy (her book’s title) is “FICTIONAL”, she insisted.

Tesolin-Mastrosa thought she had written a dark romance novel. The book’s listing described it as a “loose retelling of Cinderella”, according to Newsweek. But her readers – skilled in decoding the conventions of the genre – disagree.

A BookTok storm

For them, her “spicy” sexual romance between a very young woman, just turned 18, and a friend of her father’s, who had “noticed” her since she was only three, amounts to representation of grooming and paedophilia – and is not acceptable.

In her apology, Tesolin-Mastrosa wrote that the characters’ sexual relationship did not begin until both characters had reached the age of consent.

Things exploded on Booktok and Instagram, where videos promoting the book had attracted hundreds of thousands of views around the world. Daddy’s Little Toy, published under the pseudonym Tori Woods, spells its title out in a child’s alphabet blocks on the cover. The back blurb voices the desires of the two protagonists.

Angry Booktokkers, especially dark romance fans of age-gap erotica (almost all women) reacted quickly. They argued the book should be removed from sale (it has been) and the writer should be jailed, with her children protected from her. Those who read it should be jailed, too, some declared.

Australia’s history of book bans

But can a novel be classified as child sexual abuse material?

Both NSW and Commonwealth laws are clear. The definition of Child Abuse Material under the Crimes Act is not restricted to material “produced with an actual child, but may also include CAM [child abuse material] comprised of drawings, discussions and computer generated images”.

Citing the precedent of a 2010 case, the Judicial Commission of NSW notes that: “Whether CAM constituted by drawings or discussions is the product of fantasies or a retelling of actual events is irrelevant.”

In Australia’s expansive history of book bans and literary prosecutions, the depiction of juvenile sexuality has long exercised the censors. There has been virtually unanimous community support for protecting children from exploitation and not validating adult eroticisation of children.

Fiction books have always been a target for the policing of indecency and obscenity. Now, in our image-saturated digital society, the novel may seem a niche cultural product that sits outside the general circulation of sexual content. But it’s not immune to policing.

Fiction books have always been a target for the policing of indecency and obscenity.

Pixabay/Pexels

Fiction books have always been a target for the policing of indecency and obscenity.

Pixabay/Pexels

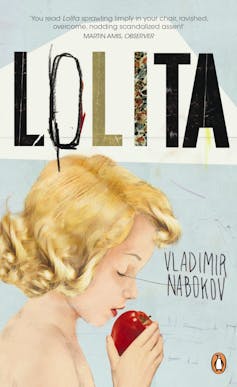

The case of Lolita

But isn’t “fiction” different from “fantasies”? What about the question of artistic merit?

Vladimir Nabakov’s Lolita, easily the most famous literary novel to feature paedophilia, was first published in 1955 by notorious libertine publisher Olympia Press, in Paris.

This fact itself immediately put it on the radar of Australia’s censors in the Department of Customs. The ban on its importation was maintained by the Appeals Censor in 1958 – and again in 1963.

Lolita was finally released in Australia in 1965, as part of an early loosening of strict book censorship. It had been the subject of substantial protest, including from prominent literary academics who were campaigning to set it for their students.

Arguments for the literary worth of Lolita point to its portrait of Humbert Humbert, its narrator, as a profoundly problematised monster. The novel does not endorse his desires, though we witness them as readers. Nabakov’s skill is in accomplishing this balance: between Humbert’s manifest obsession, written in the first person, and our realisation, as we read, that his point of view is deeply, darkly unreliable and corrupt.

In the 1960s, too, even Quadrant was prepared to insist: “such questions should be prepared to be left to the discrimination of citizens and the freedom of private debate, not mangled and messed about by public agencies”.

So, Lolita is not banned in contemporary Australia. But if you enter the title into the Australian Classification office database, 278 films, games and publications pop up: 221 of them have been classified as either Category 2 Restricted (can only be displayed for sale in adult-only venues) or Refused Classification (banned).

There is a distinct Lolita genre of erotica that highlights age-gap sex, including a subset that is child abuse material and is banned. Readers may consume non-banned versions of this genre, as consenting adults reading about consenting adults. DD/LG is the acronym (Daddy Dom/Little Girl), in the BDSM community.

In this case, a defence of literary merit is not available, as it is not provided for in the child abuse material legislation. That legislation sits separately to the legislative framework the Classification Office has historically operated under, in categorising cultural products for Australian readers and audiences, since the 1980s.

Romance’s contract with the reader

More than this, the book’s genre mitigates against such a defence. Erotic appeal – a frisson of sexualised, often taboo desire – is an implicit promise of the contract between reader and author in a dark romance novel.

Confiscated hardback copies of the novel will be “forensically examined”, the police report notes. It will be interesting to see how their reading of it may play out in a courtroom, or not, with an author who has clearly stated her remorse.

Nicole Moore has received funding from the Australian Research Council, the Australian Copyright Agency Limited and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD).

3 months ago

343

3 months ago

343

English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·