“You cannot annex another country.” This was the clear message given by the Danish prime minister, Mette Frederiksen, at a recent press conference with the outgoing and incoming prime ministers of Greenland. It did not appear aimed at Russian president Vladimir Putin, but at Donald Trump, the president of one of her country’s closest allies, who has threatened to take over Greenland.

Frederiksen, speaking in Greenland’s capitak Nuuk, was stating something that is obvious under international law but can no longer be taken for granted. US foreign policy under Trump has become a major driver of this uncertainty, playing into the hands of Russian, and potentially Chinese, territorial ambitions.

The incoming Greenlandic prime minister, Jens-Frederik Nielsen, made it clear that it was for Greenlanders to determine their future, not the United States. Greenland, which is controlled by Denmark, makes its own domestic policy decisions. Polls suggest a majority of islanders want independence from Denmark in the future, but don’t want to be part of the US.

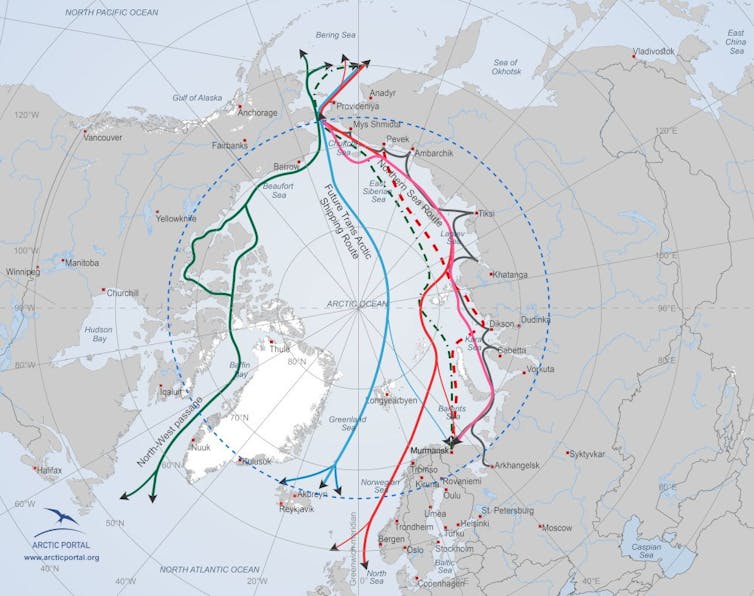

Trump’s interest in Greenland is often associated with the island’s vast, but largely untapped, mineral resources. But its strategic location is arguably an even greater asset. Shipping routes through the Arctic have become more dependable and for longer periods of time during the year as a result of melting sea ice. The northwest passage (along the US and Canadian shorelines) and the northeast passage (along Russia’s Arctic coast) are often ice free now during the summer.

Breaking the Ice: Arctic Development and Maritime Transportation, ArcticPortal.org

Breaking the Ice: Arctic Development and Maritime Transportation, ArcticPortal.org

This has increased opportunities for commercial shipping. For example, the distance for a container ship from Asia to Europe through the northeast passage can be up to three times shorter, compared to traditional routes through the Suez Canal or around Africa.

Similarly, the northwest passage offers the shortest route between the east coast of the United States and Alaska. Add to that the likely substantial resources that the Arctic has, from oil and gas to minerals, and the entire region is beginning to look like a giant real estate deal in the making.

Arctic assets

The economic promise of the Arctic, and particularly the region’s greater accessibility, have also heightened military and security sensitivities.

The day before J.D. Vance’s visit to Greenland on March 28, Vladimir Putin, gave a speech at the sixth international Arctic forum in Murmansk in Russia’s high north, warning of increased geopolitical rivalry.

While he claimed that “Russia has never threatened anyone in the Arctic”, he was also quick to emphasise that Moscow was “enhancing the combat capabilities of the Armed Forces, and modernising military infrastructure facilities” in the Arctic.

Equally worrying, Russia has increased its naval cooperation with China and given Beijing access, and a stake, in the Arctic. In April 2024, the two countries’ navies signed a cooperation agreement on search and rescue missions on the high seas.

National Snow & Ice Data Center, Arctic Portal

National Snow & Ice Data Center, Arctic Portal

In September 2024, China participated in Russia’s largest naval manoeuvres in the post-cold war era, Ocean-2024, which were conducted in north Pacific and Arctic waters. The following month, Russian and Chinese coastguard vessels conducted their first joint patrol in the Arctic. Vance, therefore, has a point when he urges Greenland and Denmark to cut a deal with the US because the “island isn’t safe”.

That the Russia-China partnership has resulted in an increasingly military presence in the Arctic has not gone unnoticed in the west. Worried about the security of its Arctic territories, Canada has just announced a C$6 billion (£3.2 billion) upgrade to facilities in the North American Aerospace Defense Command it operates jointly with the United States.

It will also acquire more submarines, icebreakers and fighter jets to bolster its Arctic defences and invest a further C$420 million (£228 million) into a greater presence of its armed forces.

Read more: Arctic breakdown: what climate change in the far north means for the rest of us

Svalbard’s future role?

Norway has similarly boosted its defence presence in the Arctic, especially in relation to the Svalbard archipelago (strategically located between the Norwegian mainland and the Arctic Circle). This has prompted an angry response from Russia, wrongly claiming that Oslo was in violation of the 1920 Svalbard Treaty which awarded the archipelago to Norway with the proviso that it must not become host to Norwegian military bases.

Under the treaty, Russia has a right to a civilian presence there. The “commission on ensuring Russia’s presence on the archipelago Spitzbergen”, the name Moscow uses for Svalbard is chaired by Russian deputy prime minister Yury Trutnev, who is also Putin’s envoy to the far eastern federal district. Trutnev has repeatedly complained about undue Norwegian restrictions on Russia’s presence in Svalbard.

From the Kremlin’s perspective, this is less about Russia’s historical rights on Svalbard and more about Norway’s – and Nato’s – presence in a strategic location at the nexus of the Greenland, Barents and Norwegian seas. From there, maritime traffic along Russia’s northeast passage can be monitored. If, and when, a central Arctic shipping route becomes viable, which would pass between Greenland and Svalbard, the strategic importance of the archipelago would increase further.

From Washington’s perspective, Greenland is more important because of its closer proximity to the US. But Svalbard is critical to Nato for monitoring and countering Russian, and potentially Chinese, naval activities. This bigger picture tends to get lost in Trump’s White House, which is more concerned with its own immediate neighbourhood and cares less about regional security leadership.

Consequently, there has been no suggestion – so far – that the US needs to have Svalbard in the same way that Trump claims he needs Greenland to ensure US security. Nor has Russia issued any specific threats to Svalbard. But it was noticeable that Putin in his speech at the Arctic forum discussed historical territorial issues, including an obscure 1910 proposal for a land swap between the US, Denmark and Germany involving Greenland.

Putin also noted “that Nato countries are increasingly often designating the Far North as a springboard for possible conflicts”. It is not difficult to see Moscow’s logic: if the US can claim Greenland for security reasons, Russia should do the same with Svalbard.

The conclusion to draw from this is not that Trump should aim to annex a sovereign Norwegian island next. Maritime geography in the north Atlantic underscores the importance of maintaining and strengthening long-established alliances.

Investing in expanded security cooperation with Denmark and Norway as part of Nato would secure US interests closer to home and send a strong message to Russia. It would also signal to the wider world that the US is not about to initiate a territorial reordering of global politics to suit exclusively the interests of Moscow, Beijing and Washington.

Stefan Wolff is a past recipient of grant funding from the Natural Environment Research Council of the UK, the United States Institute of Peace, the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK, the British Academy, the NATO Science for Peace Programme, the EU Framework Programmes 6 and 7 and Horizon 2020, as well as the EU's Jean Monnet Programme. He is a Trustee and Honorary Treasurer of the Political Studies Association of the UK and a Senior Research Fellow at the Foreign Policy Centre in London.

3 months ago

1617

3 months ago

1617

English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·