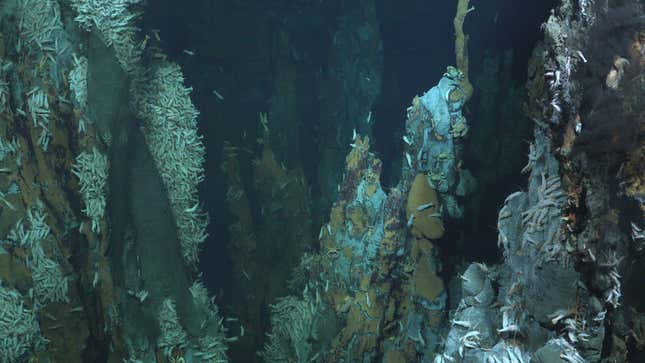

Footage taken from the Falkor(too) expedition shows a “chimney” at a hydrothermal vent thousands of feet under the ocean.Gif: Gizmodo / Schmidt Ocean Institute

A multidisciplinary team of scientists say they have discovered three new hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor along an underwater mountain range—the first of these kinds of vents discovered in decades.

Hydrothermal vents are some of the weirdest places under the sea. The vents are created when hot magma rises from between tectonic plates, then cools and creates new seafloor. The water around the magma heats up and pulls minerals from the rock, creating boiling spurts of mineral-rich water. Incredibly, despite the temperature of the water around these vents reaching an average of 700 degrees Fahrenheit (371 degrees Celsius), they’re teeming with all sorts of bizarre life. The first hydrothermal vents were only discovered in the 1970s, so scientists are still learning a lot about them.

The expedition was coordinated by the Schmidt Ocean Institute, a nonprofit that works on ocean science projects, and took place on its new research vessel, the Falkor(too). The expedition along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a huge underwater mountain range, relied on underwater robots to map out an area of the ocean floor roughly the size of Manhattan.

Only about one-fifth of the ocean floor has been mapped, so expeditions like this one are incredibly valuable to learning more about what lies beneath the sea. And the world is increasingly interested in what is going on down there. Since vents like the one the Falkor(too) mapped out are so rich in minerals, they’re key target areas for potential deep-sea mining—a solution that has been increasingly floated by various world governments to meet projected increasing demand for clean energy-related minerals. But our limited understanding of hydrothermal vents means that mining could be devastating to the incredible biodiversity they contain.

“The ocean, the atmosphere, and the land are completely connected in ways people really need to understand,” Wendy Schmidt, one of the Institute’s founders, said on the Today show on Thursday. “This challenges all of us to think of what life on Earth really is and what we need to protect.”

One of the new vents, discovered about 6,560 feet (2,000 meters) underwater on the Puy des Folles Seamount. The cloudy substance in the upper right is the hot, nutrient-rich water being expelled from the vent. Photo: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute

A closeup of shrimp swarming around the chimney.Gif: Gizmodo / Schmidt Ocean Institute

Another view of the vent. Only a quarter of the ocean floor has been mapped.Photo: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute

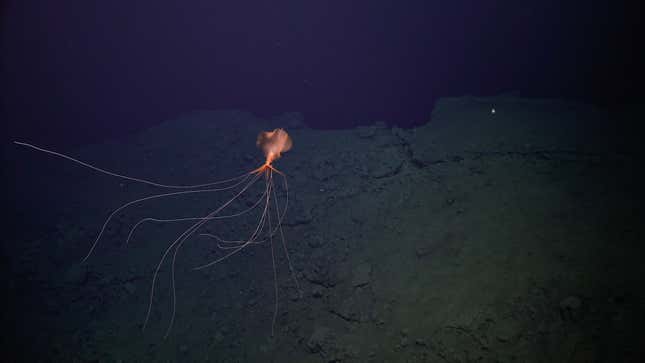

At depths like these, there are some strange creatures. The research team spotted a Magnapinna squid, otherwise known as a bigfin squid, at around 6,560 feet (2,000 meters) deep. Photo: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute

A closeup of the squid. There have been fewer than two dozen sightings of these squid, according to NOAA, and their tentacles can be several feet long. Photo: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute

A closeup of the vent. Many of the animals that live around these vents, like tube worms and mussels, feed on the nutrients and bacteria coming from the mineral-rich water. Photo: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute

Water is expelled at the vents through large stacks called chimneys; the tallest of these chimneys the researchers observed was more than 65 feet (20 meters) high.Photo: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute

Another view of the chimney.Gif: Gizmodo / Schmidt Ocean Institute

The vents were mapped using a robot known as a remotely operated vehicle, or ROV. In this photo, the ROV, dubbed SuBastian, is pulled out of the water after being in the ocean for 13 hours. The ROV was connected by a cord to the ship, allowing it to stay plugged into power and trasmit video.Photo: Mónika Naranjo-Shepherd / Schmidt Ocean Institute

David Butterfield of the University of Washington looks at video feeds coming in from the ROV. Photo: Mónika Naranjo-Shepherd / Schmidt Ocean Institute

Research Vessel Falkor(too).Photo: Schmidt Ocean Institute

English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·