The Conversation/Snapchat

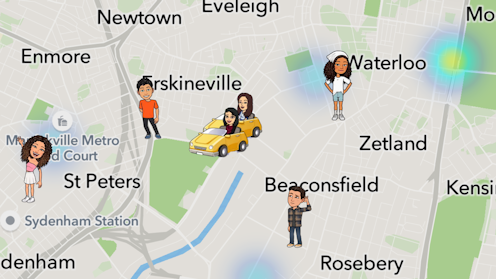

The Conversation/SnapchatLocation-sharing apps are shaping how we connect and communicate – especially among younger people. Snap Map, a popular feature within Snapchat, is widely used by teens and young adults to stay in the loop and facilitate real-time meet-ups with friends and partners.

Meanwhile, Life360 markets itself as “Australia’s number one family safety app”. It offers parents peace of mind through continuous, sophisticated location tracking.

These apps determine a person’s real-time location primarily with GPS technology that’s already in a phone. The convenience and sense of security they provide might be appealing to many people. But they can also enable stalking and other forms of coercive control.

The recent inquest into the murder of Lilie James starkly highlighted these risks. However, our research on young people’s perceptions of technology-facilitated abuse has shown many of them are not aware of the danger.

A meticulously planned murder

In October 2023, James, a 21-year-old water polo coach, was killed by her 24-year-old ex-boyfriend, Paul Thijssen, in a bathroom at St Andrew’s Cathedral School in Sydney.

James had been in a brief relationship with Thijssen. But she ended it when he became obsessed.

The coronial inquest revealed Thijssen had meticulously planned the murder. He had also used a range of coercively controlling behaviours in the lead up to his crime. For example, he physically stalked James by driving past her home on multiple occasions.

He also tracked James’s location on Snapchat to monitor her whereabouts and asked a mutual friend to keep “an eye on her” during a party she attended.

The court also heard about Thijssen’s use of abusive digital behaviours as a pattern of coercive control across his previous relationships.

Not a sign of love and care

A friend of James and Thijssen misinterpreted his tracking of her location as a sign of love and care. Young people are generally at risk of making similar mistakes, as our recent research highlights.

As part of Maria’s PhD thesis, the research included surveys with more than 1,000 respondents and follow-up focus groups with 28 young people (aged 16–25). We asked these young people about their perceptions of technology-facilitated coercive control in dating relationships.

Every young person who participated in the focus groups had either used location-sharing apps in their own relationships or knew someone who had. This reflected a high level of normalisation regarding the use of location sharing between dating partners.

Many participants underestimated the risks associated with these behaviours.

In fact, most young people in our study misinterpreted tracking a partner via Snapchat, the “Find My” app and Life360 as a protective behaviour and a sign of care and trust.

There is a high level of normalisation regarding the use of location sharing between dating partners.

Tom Wang/Shutterstock

There is a high level of normalisation regarding the use of location sharing between dating partners.

Tom Wang/Shutterstock

It starts at home

According to the young people in our study, initial experiences with location tracking often start in the family home.

In an attempt to ensure their children’s safety, parents are increasingly adopting tracking apps to monitor their children’s movements.

Our findings suggest the widespread use of location sharing within families normalises its adoption outside the home. This can lead to a greater acceptance of surveillance among young people in friendships and romantic relationships.

This observation is unsurprising when considering research from November 2024 by the eSafety Commissioner on broader community attitudes towards location sharing. It found one in ten Australians believe it is “reasonable to expect to track a partner using location-sharing apps”.

Young people in our research were able to identify common red flags of harmful location tracking – for example, obsessively monitoring a partner’s whereabouts. But they described how the normalisation of location sharing makes it challenging for them to “opt out” of sharing their location with friends and partners.

Location sharing is perceived as a demonstration of commitment in young relationships. Therefore, when someone in a relationship decides to stop sharing their location, it is seen as a sign of distrust or a breach of shared dating norms. And it may lead to displays of anger, as seen in the example of Thijssen’s earlier controlling relationships.

Apps such as Snapchat include location-sharing features.

Diego Thomazini/Shutterstock

Apps such as Snapchat include location-sharing features.

Diego Thomazini/Shutterstock

Negotiating digital boundaries early on

Location sharing is often normalised in the family context without informed conversations about the associated risks in other relationships. But opting out of location sharing with friends or partners requires the skills and confidence to have such conversations.

The Australian Government is investing A$77.6 million in respectful relationships education. This will be delivered in partnership with states, territories and non-government school sectors.

However, for this initiative to be successful, both parents and young people should be educated about digital behaviours. These behaviours include location sharing in various contexts, such as with family members, partners and friends.

Parents need to be informed about the potential risks associated with location sharing and its normalisation. Beyond learning how to use parental controls to ensure their children’s online safety, it is equally important that parents are equipped with skills to have informed conversations with their children about the risks associated with these features.

Young people also require skills to navigate difficult conversations about their own digital boundaries.

Solely relying on more education around the risks and protective measures related to location sharing, such as online stalking or increasing awareness of privacy controls, will not achieve this. We must equip young people with crucial knowledge and skills to recognise the need for, and negotiate, digital boundaries early on in their relationships.

Setting boundaries in response to experiences of technology-facilitated coercive control may require additional safeguards, including the awareness and support of family and friends.

Where technology-facilitated coercive control behaviours persist or escalate, national helplines and local domestic violence services can offer vital support, information and referral pathways.

The National Sexual Assault, Family and Domestic Violence Counselling Line – 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) – is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for any Australian who has experienced, or is at risk of, family and domestic violence and/or sexual assault.

Silke Meyer receives funding from Australia's Research Organisation for Women's Safety (ANROWS) and state government funding for research into domestic, family and sexual violence.

Maria Atienzar-Prieto does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

2 months ago

1105

2 months ago

1105

English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·